Bal Gangadhar Tilak - "Swaraj is my Birthright"

Bal Gangadhar Tilak (Marathi: बाळ गंगाधर टिळक) 23 July 1856(1856-07-23)–1 August 1920 (aged 64), was an Indian nationalist, teacher, social reformer and independence fighter who was the first popular leader of the Indian Independence Movement. The British colonial authorities derogatorily called him the "Father of the Indian unrest", a title which the Indian Nationalists paradoxically considered a badge of Honor. He was also conferred upon the honorary title of "Lokmanya", which literally means "Accepted by the people (as their leader)".

Tilak was one of the first and strongest advocates of "Swaraj" (complete independence) in Indian consciousness. His famous quote, "Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it !" is well-remembered in India even today.

Early life

Tilak was born in Madhali Alee (Middle Lane) in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra, into a middle class Marathi Chitpavan Brahmin family. His father was a famous schoolteacher and a scholar of Sanskrit. Unfortunately, he passed away when Tilak was sixteen. His brilliance rubbed off on young Tilak, who graduated from Deccan College, Pune in 1877. Tilak was among one of the first generation of Indians to receive a college education.

Tilak was expected, through Brahmin Marathi tradition, to actively participate in public affairs. He believed that “Religion and practical life are not different. To take to Samnyasa (renunciation) is not to abandon life. The real spirit is to make the country your family instead of working only for your own. The step beyond is to serve humanity and the next step is to serve God.” This dedication to humanity would be a fundamental element in the Indian Nationalist movement.

After graduating, Tilak began teaching mathematics in a private school in Pune and later became a journalist. He became a strong critic of the Western education system, feeling it demeaned the Indian students and disrespected India's heritage. He organized the Deccan Education Society with a few of his college friends, including Gopal Ganesh Agarkar, Mahadev Ballal Mamjoshi and Vishnu Krishna Chiplonkar whose goal was to improve the quality of education for India's youth. The Deccan Education society was set up to create a new system that taught young Indians nationalist ideas through an emphasis on Indian culture. Tilak began a mass movement towards independence that was camoflauged by an emphasis on a religious and cultural revival. He taught Mathematics at Fergusson College.

Political career

Journalism

Tilak co-founded two newspapers with Gopal Ganesh Agarkar, Vishnushastri Chiplunakar and other colleagues: Kesari, which means "Lion" in Sanskrit and was a Marathi newspaper, and 'The Maratha', an English newspaper in 1881. In just two years 'Kesari' attracted more readers than any other language newspaper in India. The editorials were generally about the people's sufferings under the British. These newspapers called upon every Indian to fight for his or her rights.

Tilak used to say to his colleagues: "You are not writing for the university students. Imagine you are talking to a villager. Be sure of your facts. Let your words be clear as daylight."

Tilak strongly criticized the government for its brutality in suppressing free expression, especially in face of protests against the division of Bengal in 1905, and for denigrating India's culture, its people and heritage. He demanded that the British immediately give Indians the right to self-government.

Indian National Congress

Tilak joined the Indian National Congress in the 1890. He opposed its moderate attitude, especially towards the fight for self government.

In 1891 Tilak opposed the Age of Consent bill. The act raised the age at which a girl could get married from 10 to 12. The Congress and other liberals supported it, but Tilak was set against it, terming it an interference with Hinduism. However, he personally opposed child marriage, and his own daughters married at 16.

When in 1897, plague epidemic spread from Mumbai (then Bombay) to Pune, the Government became jittery. The Assistant Collector of Pune, Mr. Rand, and his associates employed extremely severe and brutal methods to stop the spread of the disease by destroying even "clean homes." Even people who were not infected were carried away and in some cases, the carriers even looted property of the affected people. When the authorities turned a blind eye to all these excesses, furious Tilak took up the people's cause by publishing inflammatory articles in his paper Kesari, quoting the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, to say that no blame could be attached to anyone who killed an oppressor without any thought of reward. Following this, on 27 June, Rand and his assistant were killed. Tilak was charged with incitement to murder and sentenced to 18 months' imprisonment. When he emerged from prison, he had was revered as a martyr and a national hero and adopted a new slogan, "Swaraj (Self-Rule) is my birth right and I will have it."

Following the partition of Bengal in 1905, which was a strategy set out by Lord Curzon to weaken the nationalist movement, Tilak encouraged a boycott, regarded as the Swadeshi movement.

Tilak opposed the moderate views of Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and was supported by fellow Indian nationalists Bipin Chandra Pal in Bengal and Lala Lajpat Rai in Punjab. They were referred to as the Lal-Bal-Pal triumvirate. In 1907, the annual session of the Congress Party was held at Surat (Gujarat). Trouble broke out between the moderate and the extremist factions of the party over the selection of the new president of the Congress. The party split into the "Jahal matavadi" ("Hot Faction," or extremists), led by Tilak, Pal and Lajpat Rai, and the "Maval matavadi" ("Soft Faction," or moderates).

Arrest

On 30 April 1908 two Bengali youths, Prafulla Chaki and Kudiram Bose, threw a bomb on a carriage at Muzzafurpur in order to kill a District Judge Douglass Kenford but erroneously killed some women travelling in it. While Chaki committed suicide when caught, Bose was tried and hanged. Tilak in his paper Kesari defended the revolutionaries and called for immediate Swaraj or Self-rule. The Government swiftly arrested him for sedition. He asked a young Muhammad Ali Jinnah to represent him. But the British judge convicted him and he was imprisoned from 1908 to 1914 on the Andaman Islands. While imprisoned, he continued to read and write, further developing his ideas on the Indian Nationalist movement.

Much has been said of his trial of 1908, it being the most historic trial. His last words on the verdict of the Jury were such: "In spite of the verdict of the Jury, I maintain that I am innocent. There are higher powers that rule the destiny of men and nations and it may be the will of providence that the cause which I represent may prosper more by my suffering than my remaining free". These words now can be seen imprinted on the wall of Room. No. 46 at Bombay High Court.

Life after prison

Tilak had mellowed after his release in June 1914. When World War I started in August, Tilak, cabled the King-Emperor in Britain of his support and turned his oratory to find new recruits for war efforts. He welcomed The Indian Councils Act, popularly known as Minto-Morley Reforms which had been passed by British parliament in May 1909 terming it as ‘a marked increase of confidence between the Rulers and the Ruled’. Acts of violence actually retarded than hastened the pace of political reforms, he felt. He was eager for reconciliation with Congress and had abandoned his demand for direct action and settled for agitations ‘strictly by constitutional means’ - a line advocated his rival- Gopal Krishna Gokhale since beginning.

All India Home Rule League

Later, Tilak re-united with his fellow nationalists and re-joined the Indian National Congress in 1916. He also helped found the All India Home Rule League in 1916-18 with Joseph Baptista, Annie Besant and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. After years of trying to reunite the moderate and radical factions, he gave up and focused on the Home Rule League, which sought self rule. Tilak travelled from village to village trying to conjure up support from farmers and locals to join the movement towards self rule. Tilak was impressed by the Russian Revolution, and expressed his admiration for Lenin.

Tilak, who started his political life as a Maratha protagonist, during his later part of life progressed into a prominent nationalist after his close association with Indian nationalists following the partition of Bengal. When asked in Calcutta whether he envisioned a Maratha type of government for Free India, Tilak replied that the Maratha dominated Governments of 17th and 18th centuries were outmoded in 20th century and he wanted a genuine federal system for Free India where every religion and race were equal partners. He added that only such a form of Government would be able to safe-guard India's freedom.

Social contribution

In 1894, Tilak transformed worshipping Ganesha into Ganesh Chaturthi, a replacement counterpart to Muharram observance. It is touted to be an effective demonstration of festival procession. The following was the devotional song sung during the festivities.

“ Oh! Why have you abandoned today the Hindu religion?

How have you forgotten Ganapathi, Shiva and Maruthi?

What have you gained by worshipping the tabuts?

What boon has Allah conferred upon you

That you have become Mussalmans today?

Do not be friendly to a religion which is alien

Do not give up your religion and be fallen

Do not at all venerate the tabuts,

The cow is our mother, do not forget her. ”

Upon the inception of Ganesha Chaturthi, Hindus abandaoned participating Muharram festival and instances of riots were reported when the musicals passed mosques in Poona in 1894 and Dhulia in 1895.

Later years and legacy

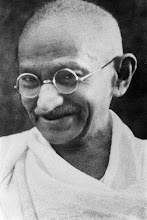

Gandhi was a true follower of Tilak's legacy.There is almost a continuation of the thought process from Tilak to Gandhi that shaped the future of the independence movement that followed. He favored political dialogue and discussions as a more effective way to obtain political freedom for India.

After Tilak’s death on August 1st, 1920, on the first day of Gandhi’s first non-cooperation campaign, Gandhi paid his respects at his cremation in Mumbai, along with 20,000,000 people[citation needed]. Gandhi called Tilak "The Maker of Modern India". The court which convicted Tilak bears a plaque that says, " The actions of Tilak has been justified as the right of every individual to fight for his country. Those two convictions have gone into oblivion -- oblivion reserved by history for all unworthy deeds".

Books

In 1903, he wrote the book Arctic Home in the Vedas. In it he argued that the Vedas could only have been composed in the Arctics, and the Aryan bards brought them south after the onset of the last Ice age.

Tilak also authored 'Shrimadbhagwadgeetarahasya' - the analysis of 'Karmayoga' in the Bhagavadgita, which is known to be gist of the Vedas and the Upanishads.

Other collections of his writings include:

The Hindu philosophy of life, ethics and religion (published in 1887).

Vedic chronology and vedanga jyotisha.

Letters of Lokamanya Tilak, edited by M. D. Vidwans.

Selected documents of Lokamanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak, 1880-1920, edited by Ravindra Kumar.

References

1. ^ Bal Gangadhar Tilak Biography - Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak Indian Freedom Fighter - Bal Gangadhar Tilak History - Information on Bal Gangadhar Tilak

2. ^ D. Mackenzie Brown. “The Philosophy of Bal Gangadhar Tilak: Karma vs. Jnana in the Gita Rahasya.” Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 17, no. 3. (Ann Arbor: Association for Asian Studies, 1958), 204.

3. ^ D. D. Karve, “The Deccan Education Society” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 20, no. 2 (Ann Arbor: Association for Asian Studies, 1961), 206-207.

4. ^ Michael Edwardes, A History of India (New York: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, 1961), 322.

5. ^ Ranbir Vohra, The Making of India: A Historical Survey (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, Inc, 1997), 120

6. ^ Encyclopedia of Asian History. “Tilak, Bal Gangadhar,” (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons And Macmillian Publishing Company 1988), 98.

7. ^ Encyclopedia of Asian History. “Tilak, Bal Gangadhar,” (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons And Macmillian Publishing Company 1988), 98.

8. ^ M.V.S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front - Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 82

9. ^ Hindu-Muslim Relations in British India, G. R. Thursby, p89,Google book

10 ^ A Concise History of Modern India Barbara Daly Metcalf, Thomas R. Metcalf, p 150-151, Google book ^ Encyclopedia of Asian History. “Tilak, Bal Gangadhar,” (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons And Macmillian Publishing Company 1988), 98.

Dadabhai Naoroji - He sought to reform the socio-political structure of India

Dadabhai Naoroji - He sought to reform the socio-political structure of India